Las plazas ágora se extienden hasta donde por clima son posibles y desaparecen más allá de donde se puede cultivar la vid. Pero ¿qué pasaría si pudiéramos bañar 850m2 de Helsinki con el sol del Mediterráneo y aumentar 13 grados la temperatura en el exterior?

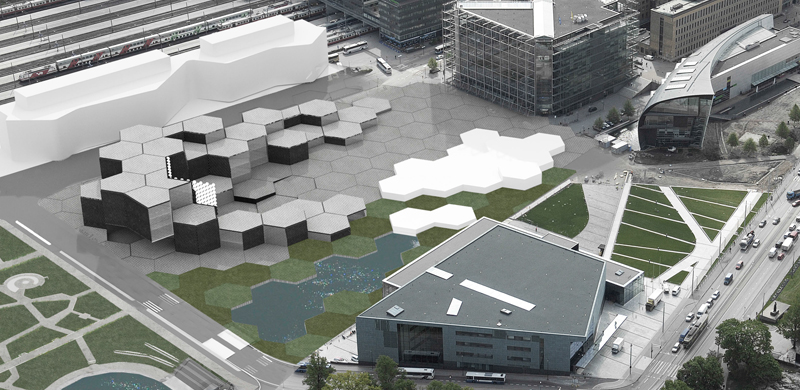

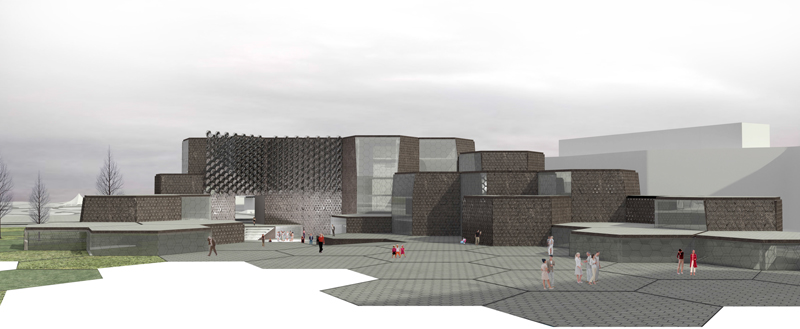

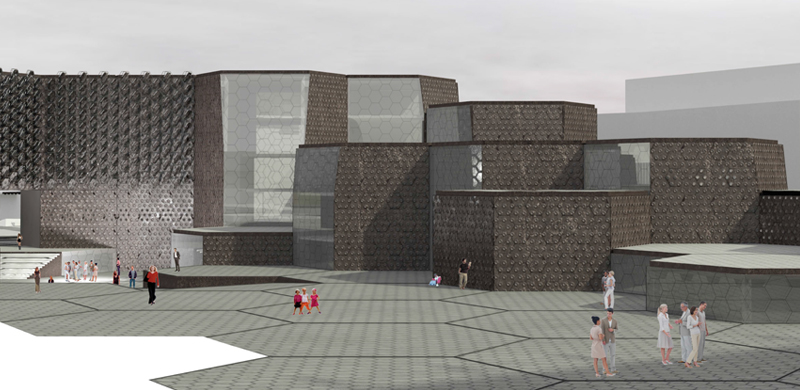

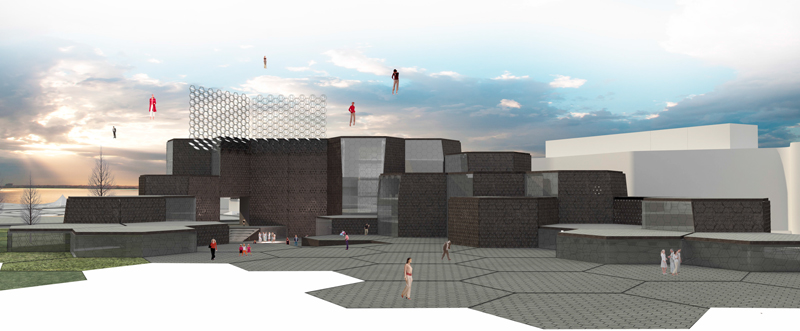

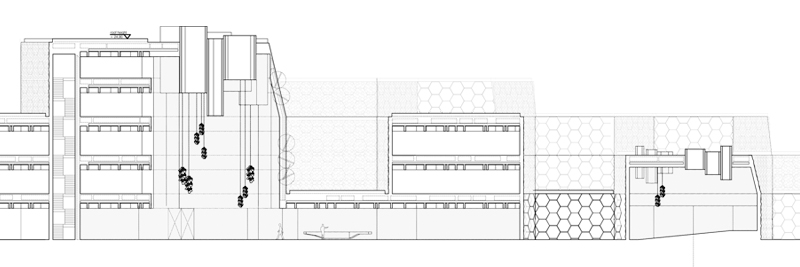

La biblioteca es un edificio escalonado que se cierra en sí mismo, rodeando dicha plaza-ágora en la que se encuentra el acceso principal a la biblioteca y la puerta hacia el paisaje abierto.

Si arquímedes pudo usar con éxito el sol para quemar las naves que amenazaban Siracusa, ¿porqué no usar el principio de los espejos orientados (en este caso con un reloj solar) para concentrar su energía ilimitada y sin coste en nuestro Ágora?

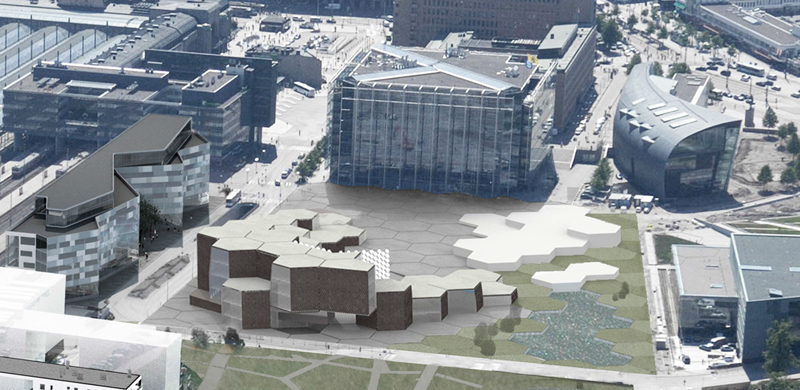

El lugar propuesto por las bases del concurso tendría que abrirse a una cuña de espacio libre flanqueada por otros importantes equipamientos de Helsinki: la Casa de la Música, el Kiasma, y también edificios valiosos como el parlamento y el Finlandia Hall de Aalto. En lugar de eso nuestra propuesta propone un edificio que cierre una plaza previa a modo de vestíbulo del parque y que convierta al espacio público en un lugar de reconocimiento, comunicación y celebración: lo que los griegos llamaban Ágora.

Keskustakirjasto Memo

The central library building, Auringon Agora, is a built landscape at the edge of Helsinki’s urban core. It is an interface between the city and the Töölö lake green area. Is it a park? Or is it a building? It is both, and many other things too.

The largest living form known on earth is a species that shares some of the qualities of a vegetable and of the mineral ground where it grows. It is called Armillaria Ostoyae, an underground mushroom to be found in Oregon’s ancient forests. It sprang up from a single spore small enough not to be seen without a microscope and has spread out for more than 2,400 years, covering up to 880 hectares nowadays.

Buildings are not living beings –they only house them–, but buildings undoubtedly “behave” for they perform over time. The lifecycle of built objects is becoming increasingly important in present times wherever anthropogenic material and energetic footprint, –especially the one related to buildings–, needs to be reduced and optimised. We, as architects, cannot predetermine the future life-performance of buildings, but we do set the main rules for their material outputs and footprint.

Any living organism on earth is a specific portion of matter that behaves over time. Life relies on complex mollecular combinations. The geometry of these combinations is also determinant for their optimal performance.

The new library building site completes the urban fabric to the Töölö park north of the Sanoma building, between Mannerheimintie West and the Elielinaukio East.

Its particular situation between the dense city centre and the open Töölö park space demands an exclusive solution beyond the limits of the proposed building plot and its geometrical restrictions.

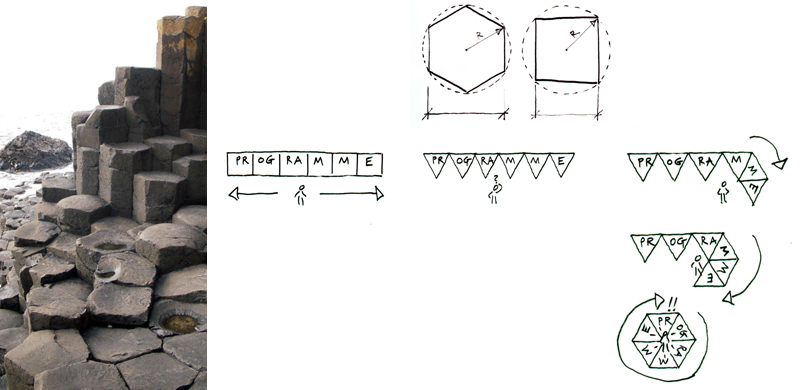

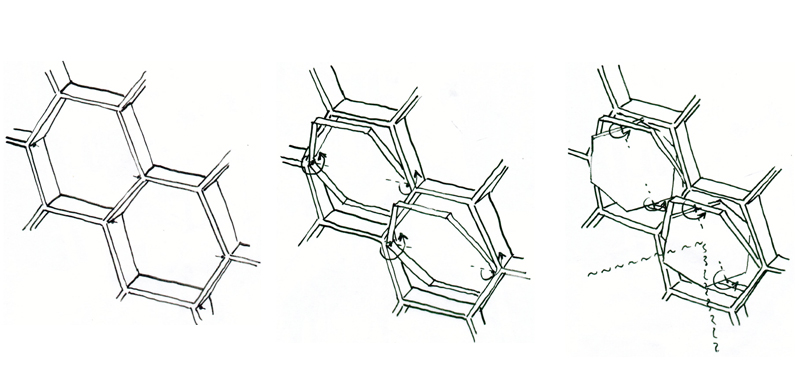

There are several reasons that let us favour a hexagonal solution over a right-angled one.

Looking north from the city towards the Töölö lake and the park area around it, three building chains can be observed springing off the city. A first chain is formed by the Kiasma, the Music Hall and the Finlandia Hall along Mannerheimintie. The second chain being the building row between Mannerheiminaukio and Elielinaukio plus the Sokos Hotel building, the Post building and the Sanoma building, A third chain is lined-up by the new mixed-use building along the railway tracks.

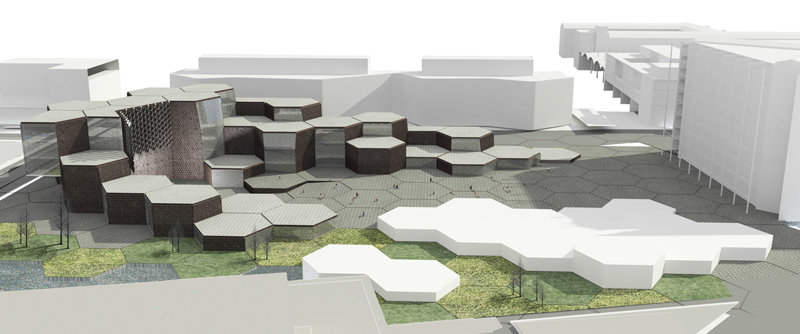

The main basic element, the “cell” of the Keskustakirjasto building plan, is a sixteen-metre-wide regular hexagon. Comparing this hexagon geometry with a regular square, both inscribed within a circle with equal perimeter, the hexagon has a notably bigger area, thus helping to improve the shape ratio and the energy balance of the whole building. Furthermore, the obtuse 120-degree angle of the hexagon softens the corners of the building and by doing so, it also provides for a better integration into the surrounding site.

The building is therefore conceived as a bottom-up approach which assembles together cell units to form the whole, instead of considering a preset envelope where to box the content.

A hexagonal geometry has another very important value: It better answers to a complex programme of a library where the open and noisy spaces of the public sphere have to coexist side by side with other smaller spaces for private use.

A building that is composed out of small hexagonal units is more fractal than linear. Its spaces, its whole stuff –from the envelope to the furnishing- really “turn around” their users

Shaped as if huge basaltic steps, the pedestrian street-level of the city unfolds and shows increasing height from south to north and from west to east, offering more irradiation surface towards the sunnier regions of the sky while compacting and densifying the built volume towards north and east.

The result of the building is a sum of parts which looks like a huge crystal landscape.

More than a park, the Makasiinpuisto area happens to be a big connection space for the city.

In our proposal, a bright “agora” articulates the open park space North and the city space South, serving as a shared entrance both to the park and to the library when approaching them from the city. The geomorphic built volumes of the library encircle and enclose this space from all sides except South, where it becomes open facing the city and the Sanomatalo and responding spatially to the imposing void of its foyer. As the result of occupying the Makasiinpuisto area, the existing Magazine structure will have to be demounted and rebuilt again, i.e. at the Seurasaari open air museum, so achieving a honourable part in the built heritage of Finland.

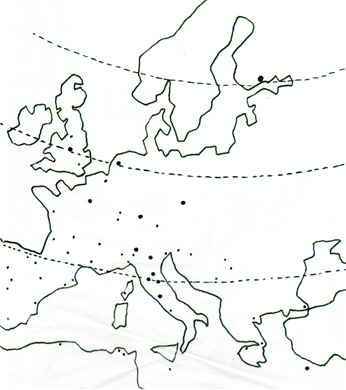

As mentioned in the guidelines of this competition, the main aim of the central library should be to become a “warm welcoming piazza”. Public open meeting spaces, catalysts of urban life are not a common case in most northern countries’ cities. In such boreal climates those spaces can only be used intensely around summer. The rest of the year, due to extreme outdoor weather conditions, urban life is forced to move behind windows and walls. Helsinki has impressive esplanades and beautiful urban parks, and there are a few busy urban corners such as the one facing Stockmann, where Mannerheimintie meets Aleksanterinkatu, but unfortunately in H:ki there aren’t any forum or agora-piazzas; the kind of spaces where philosophy bloomed some 25 centuries ago, and where democratic patterns were spotted at first.

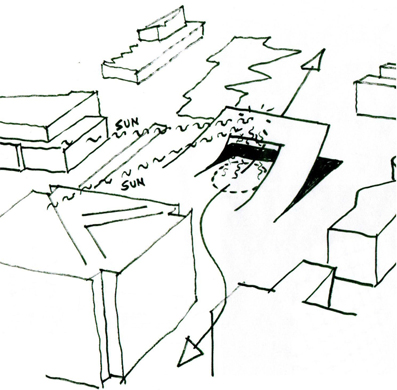

During the very initial inception stages, it appeared to us that this urban-climatic paradox really should become part of the core-design concept. The very sense of place/piazza leans on an open air lukewarm space where people can meet, chat, challenge themselves, tell stories and listen comfortably to each other.

Would it not be a gentle extravagance, and an emblem of the vital nature of cultural life in Helsinki, if one could build, –and use for at least 9 months a year–, a public open space in which social exchange could effectively take place?

Agora-like Public open spaces can be found in Europe reaching as far North as wine-regions extend. Once assumed that Alko Oy has managed to import wine into Finland, we now vote for getting the Mediterranean sun shining on 850 square metres of Finnish grounds.

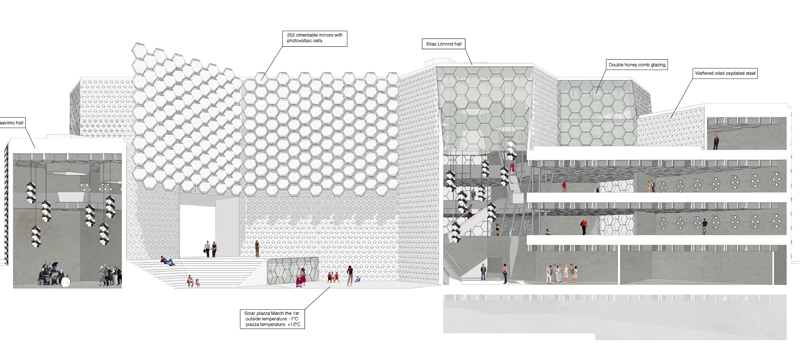

Solar gain as a social benefit: by skilfully placing solar deflectors within a limited area, a temperature gain of more than 13°C can immediately be achieved when sunny (up to 10º with average weather, see environmental engineer report), and thus, 9 successful months/yr of an effective use of the place can be guaranteed.

Mirrors which function as sun deflector panes are installed on top of the plaza, provided with a Cardan suspended drive that follows the daily sun path. If needed the panes can be raised-up mechanically to catch the low sun rays from the north during the summer.

The solar deflectors are double-panelled mirror surfaces, composed by a reflective panel covering photovoltaic panels behind. This double-use solar technology serves both to heat-up the solar piazza and also to produce approx. 16% of the total electic energy demand of the building (see also HVAC Report).

The hexagonal geometry of the building influences mainly the spatial experience: it is more spinning than linear. Its spaces, its whole stuff –from the envelope to the furnishing– really “turn around out” their users.

Visitors feel everywhere as if they would be in their own private “castle tower”. The library “embraces” at once its occupants inside, and the space of the city outside.

At street level, the building rises out from the ground creating dramatic relationships between inside and outside spaces. Crossing from Mannerheimintie, visitors face first the cafeteria that invites to calmly read a book while sipping a coffee. Coming from the Rautatiasema we first meet the restaurant with its jazzy annex. Both could develop to the most important literary live spots in Northern Europe.

All the public spaces at ground level (main lobby, main event spaces, information and other public services) surround the piazza, which acts as a kind of free enclosure space with an outside feeling but an inside climate, intimately connected with the activity taking place in the building.

The Cinema and the the Multihall are placed behind the foyer, so that they can be easily enjoyed, maybe together with the piazza, also when the library is closed. The cinema projection theatre/auditorium is located next to the reception hall and the pick-up area. The people will access the auditorium seating area from an intermediate level. The stage is placed one half level below access level. Further back, the most distant seats in the auditorium are located one half level above access level, thus one full level above the stage. Below those far-end seating rows, a backstage space is proposed for the Multihall space; additional storage area is provided annex to the stage. The rows are mounted on a collapsible structure that folds back against the Alvaraalonkatu façade wall.

The main library spaces and all associated spaces are housed along the 2nd and 3rd floor of the library.

Oases and Quiet Areas which include their own “lightweight mezzanines” are strategically placed, most of them deppressed 70 cm from standard floor level, along various perimetral areas along the 2nd and 3rd floor of the library. This gives the users a special and uniquely simple sense of “distance” and “shelter” within the overall plan, even more intense when stepping up to the mezzanine wooden “hanseatic cells”: Here one can see without being seen, overview space from above, working in full concentration (Quiet Areas).

The main hexagonal layout of the building helps daylight to flow through. No reading or working area lacks of it. Main voids throughout all levels help visitors to orientate themselves and relate spaces between levels.

The Living Lab occupies a privileged position at level 2 on the West aisle, from there everybody can see and be seen. As its complement, the Children’s World occupies the biggest part of level 5 and is where the “castle tower feeling” is as strongest, a bright, roof-lit area on top of the building.

One of its features besides its panoramic view is the “solar mirror belvedere”, a large window South facing towards the city and the solar deflectors.

The roof terraces complement seasonally the functions of the building: during summer they can be used as an extension of the interior activities, during winter the snowed surfaces additionally help to lighten the interior during weak daylight.

The total energy consumption/demand in our proposed buiding is just 86 KW/year/m². This represents an additional 30% efficiency increase if compared to the actual competition briefing energy demand reference of 120 KW/year/m².